Morph 2022

“I intend to speak of forms changed into new entities”

– Ovid, Metamorpohosis, line 1 & 2

In Ovid’s epic poem Metamorphosis Daphne, the mythological nymph of Arcadia, becomes a universal symbol of imperial power through victory. But not her own. Her total transformation into a laurel tree to escape Apollo’s advances, causes her to lose her sense of self and her autonomy. She is henceforth paraded as a symbol of Apollo’s victory and the name ‘Daphne’ is never mentioned in the poem again.

The exhibition Morph investigates the ambiguous and changeable nature of power. It considers our perception of power over, or in relation to another person, creature, vegetation or land area at a given time and how this can be overturned, depending on random and unstable circumstances. It also questions traditional translations of gender expectations in terms of power monopolization: the powerful male as opposed to the weak female. Transformations or metamorphoses, especially as it is viewed through mythology, are used as metaphors for power thus lost or gained.

Transformation is an essential theme in folklore and religious material. In mythology, power could instantly be enhanced or destroyed when a person was transformed into a mixed or pure animal form (theriomorphic transformation) or vegetable form (phytomorphic transformation). Change often involved a transition period in which boundaries were broken and chaos ruled, only to be overcome as order was restored. The theriomorphic form in itself could also be associated with a manifestation of chaos - something which does not fit into the natural order of things similar to a taboo, for example monsters in demonic traditions.

But, the opposite in some cases was also supposed to be true: that of new life obtained by breaking through acceptable bounds and the abolition of the order of the old for example transformations in creation myths or transformations of self for the purpose of transcendence.

In contemporary times and with the rise of environmentalism we have a more sympathetic view about transmogrification as depicted in popular culture. We ‘worship’ fictional super heroes in possession of animal-like powers or empathise with hybrids when allowed to be audience to their private inner turmoil.

Yet, little more than a century ago women especially, if not reconciled to the role of mother and housewife, were surprisingly often viewed as a “predatory beast” in the form of the “femme fatale”. Examples of titles of literary works by Baudelaire during that time, in which females were the main characters, give us clear examples: “The metamorphoses of the vampire”, “The dancing serpent” and “The flowers of evil”, to name a few.

Gender expectations are still rigid today in many instances, allowing for little allowance for strength in women or weakness in males.

Morph consists of a collection of figurative pastel and charcoal drawings, relief printing and mixed media artworks depicting vulnerable male nudes and women portraits and nudes. The exhibition also includes a series of plant and animal drawings and abstract ‘de-constructed’ artworks.

The portrait drawings are for the most part depictions of Daphne, an example of a tragic and weak figure whose transformation can only be viewed as something which gave her transgressor an even stronger hold or power over her. Yet, the strength of women, more than their weaknesses is celebrated in this exhibition: The iris flower as a symbol for women’s strength was a popular design feature during the Art Nouveau period - the same period in which ideas of woman as a femme fatale abounded. A sensual and dangerous looking plant, almost like Georgia O’Keeffe’s closely cropped paintings of flowers, which were accepted by the art public of her day to be depictions of female genitalia – a view which she, by the way, strongly rejected throughout her whole life.

The iris flower is named after the mythological goddess Iris, a messenger goddess who used her rainbow and golden wings for communication between different mythological gods or as a vehicle for communication between humans (especially women) and the heavenly spheres. Similarly, pigeons, birds or any winged creature, were viewed as vehicles for messages or spiritual communication. As such there are several drawings of birds included in this exhibition

Eve is also depicted with a skeleton of a serpent (or devil in animal form) in her hair as the personification of the first femme fatale (according to many).

A large portrait of a woman holding an AK-47 rifle and surrounded by floral motifs and palm fronds, is imagery often used in contemporary African art and is fast becoming a classical symbol of the strong nurturer who can defend herself, her family and her natural environment. She represents the actual situation in which many African and middle Eastern women find themselves today. The image was adapted from a media photograph of an Afghan girl who shot and killed six Taliban members who killed her parents, thereby saving herself and her younger brother from kidnapping. This is a real life example of the weak female drastically transformed in her re-possession of power.

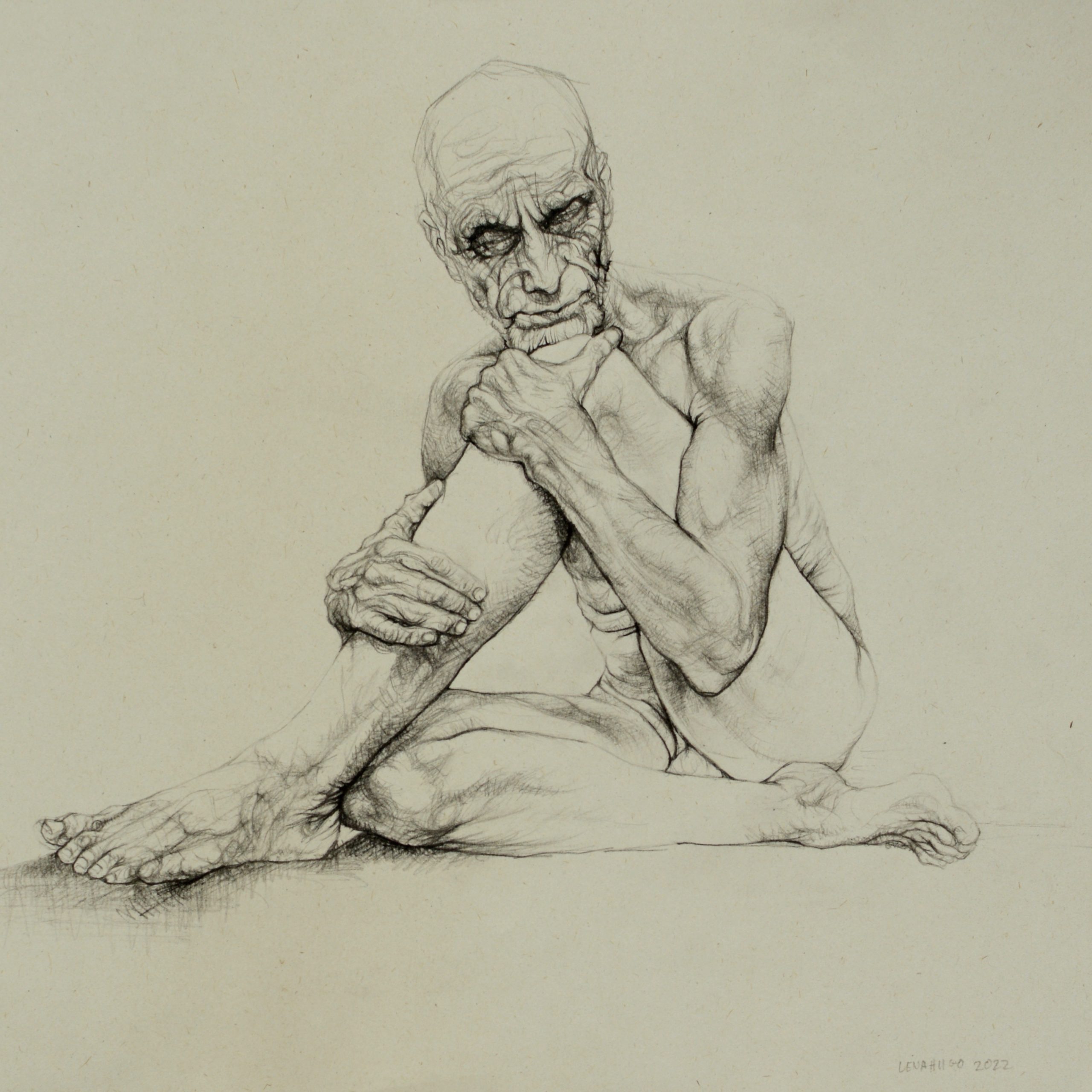

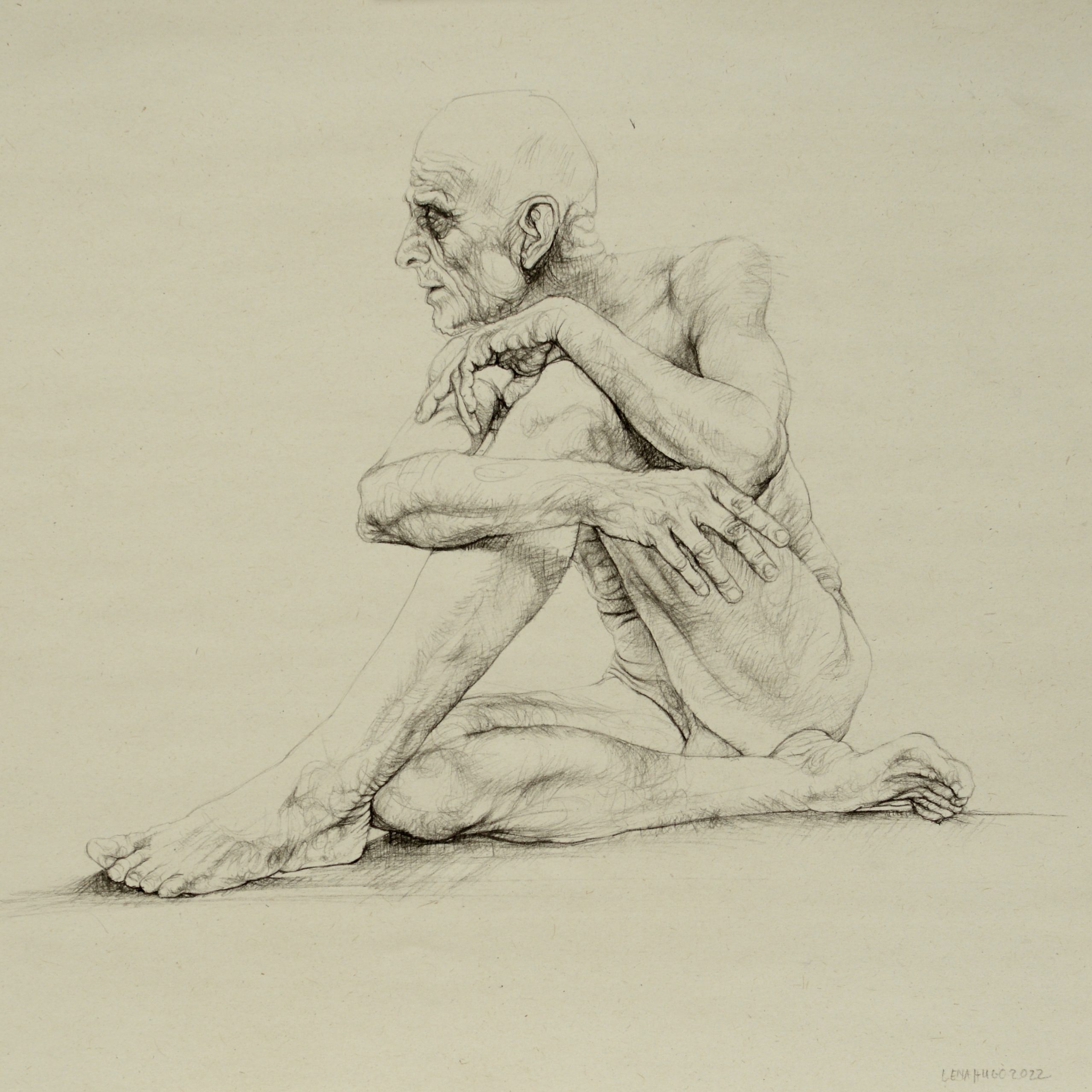

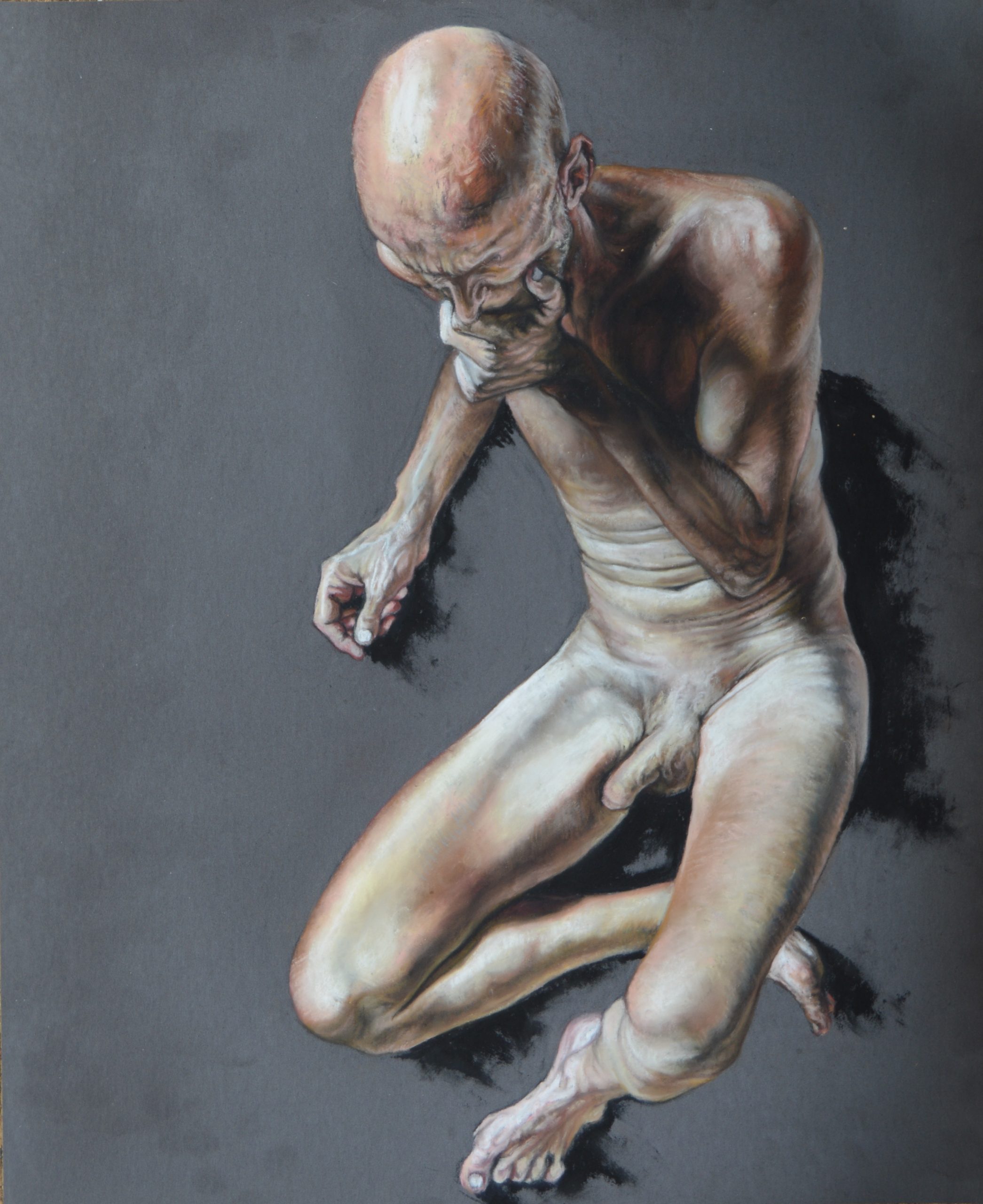

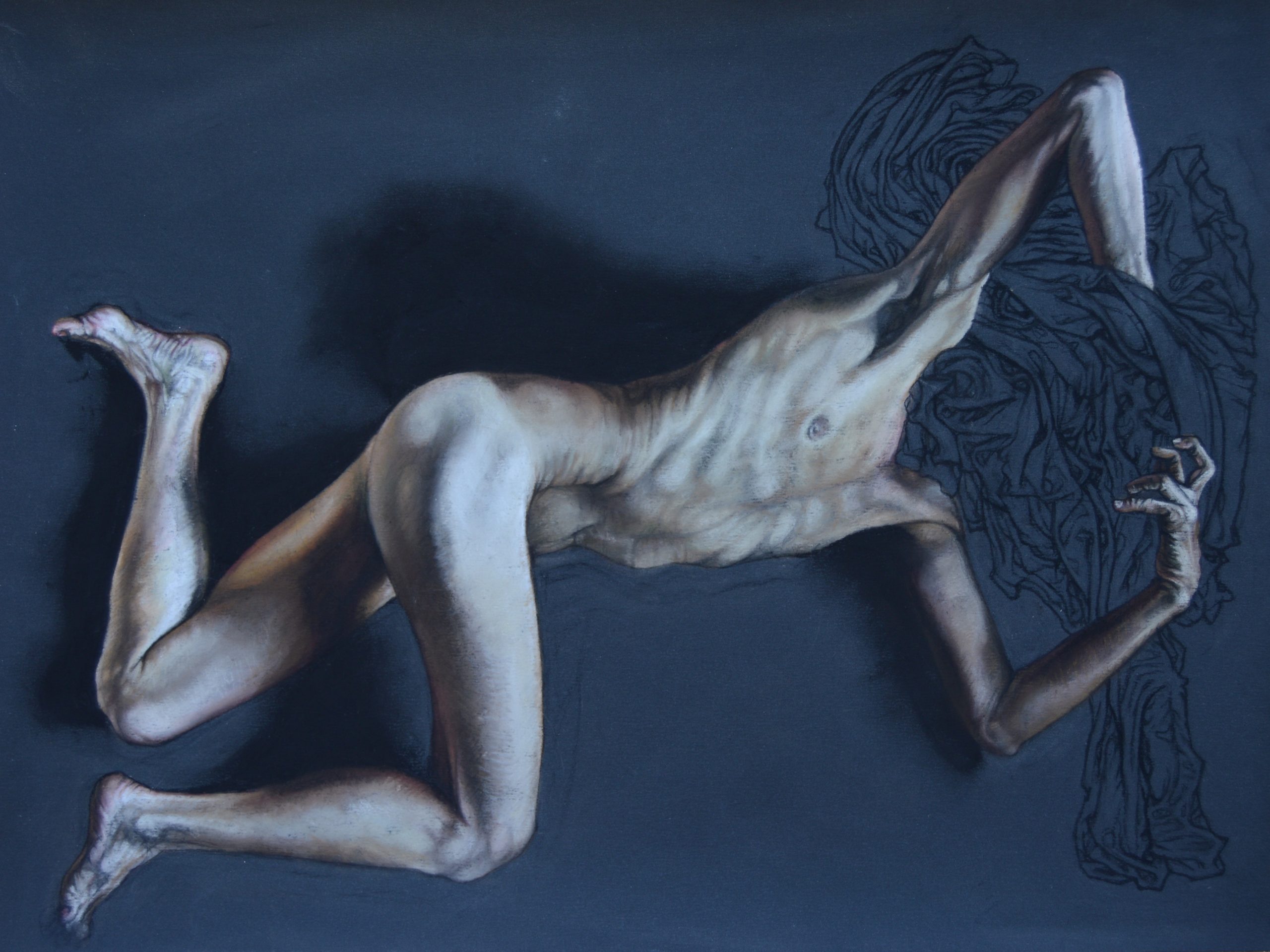

A part of the exhibition is also devoted to the fragile male. Male as fragile, not because of any feminist propensities on the part of the artist, but rather because of an acknowledgement, in empathy, of his weaknesses. To view the cosmos lashing out its capricious onslaughts against male and female alike and in the same measure, is to acknowledge the human condition in its totality. Male nudes are here often depicted sharing the picture plane with twisted pieces of draperies or cloth resembling a bed sheet, often knotted. This may represent an evil presence in the form of a nightmare or an intruder or something that will tie and bond. In mythology, men were equally harassed by enemies or over-zealous lovers and often faced the penalty of being abducted, raped or transformed into an animal- or plant form.

A series of de-constructed artworks represent that in-between state of chaos and consequential transformation. Artworks were taken apart or destroyed and re-assembled as a metaphor for birth, new life, complete change and a new order.

__________

In the wonderful and mysterious world of nature, animals can hide from predators or predators can lure their prey, by pretending to be what they are not, by “transforming” themselves into something attractive, disgusting, invisible or even something resembling a different species. When an animal can utilise this ability successfully, or otherwise, recognize the deception in time (when on the receiving end), it may mean the difference between life and death in the animal kingdom.

We don’t have the ability to transform ourselves physically to evade and survive invasion or assault or to readjust ourselves to a changing world. But we may attempt -if we dare- to subtly adapt or completely transform our spirit, which is waiting for us in that inner most and untouchable anteroom - our sacrosanctum.

There is hope for us, to survive and to be resilient and creative, in the face of peril and external change.

20 March - 1 May, Gallery at Glen Carlou, Klapmuts, Western Cape

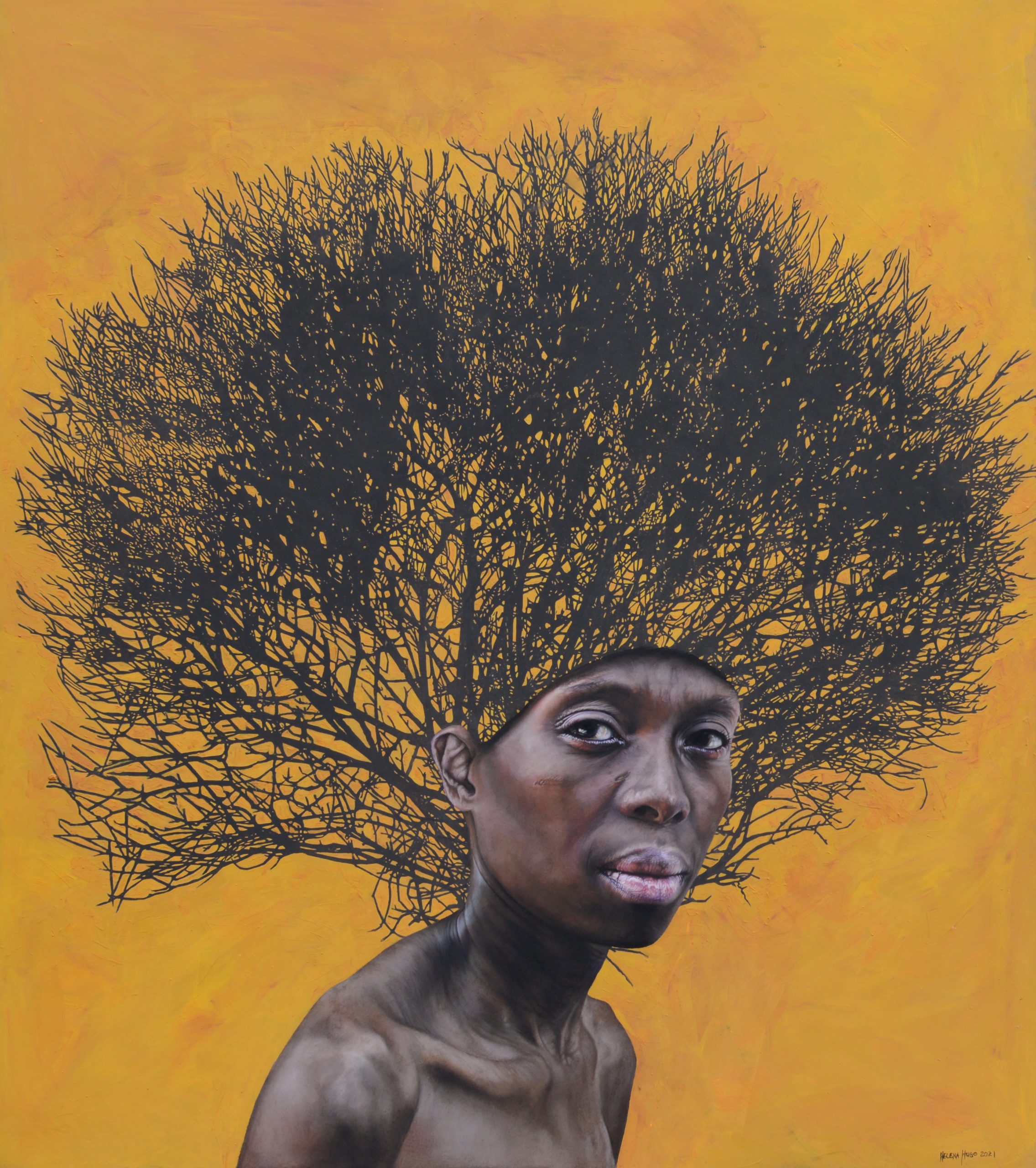

Daphne IV, 122cm x 88cm, pastel, lino print and acrylic paint on board

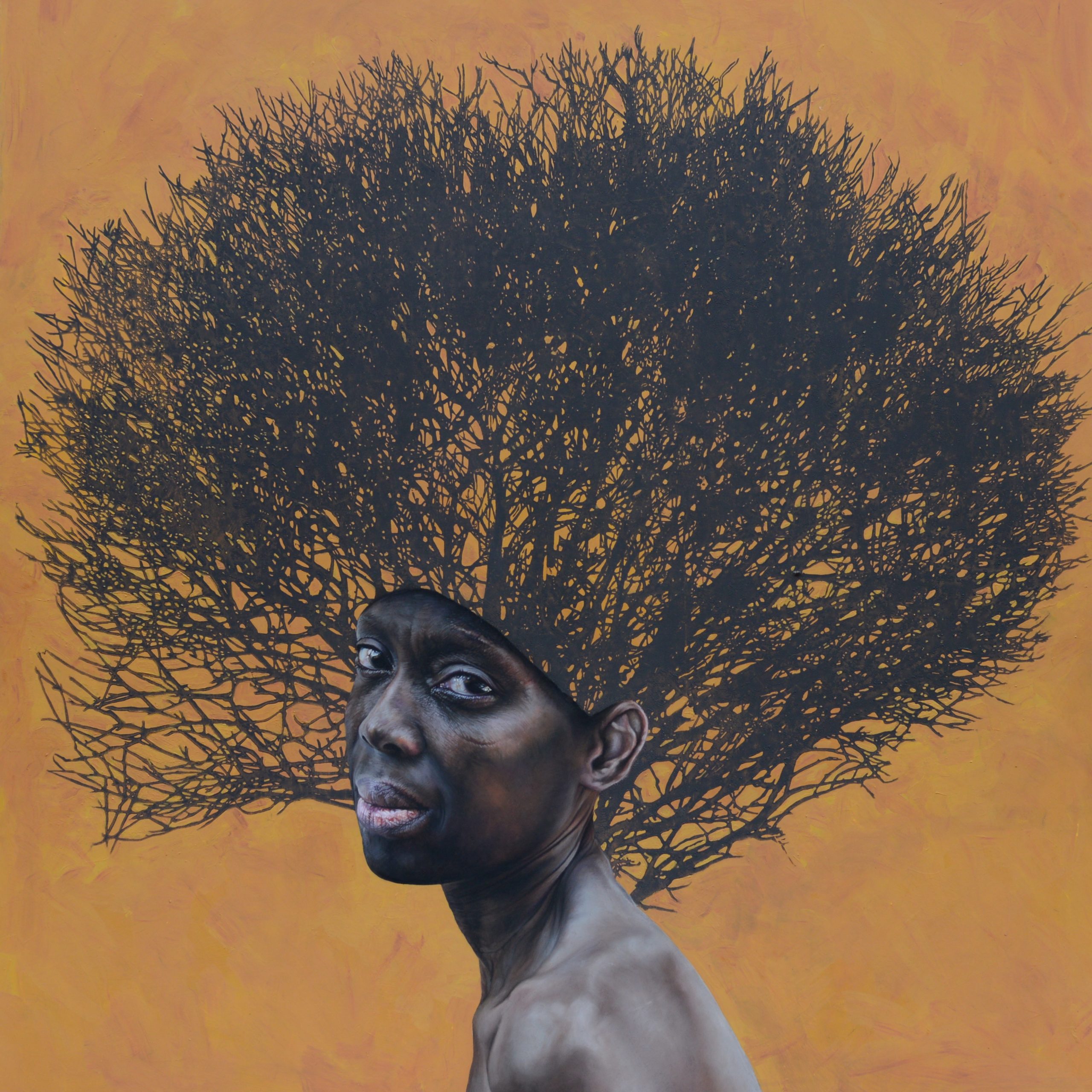

Daphne IV, 122cm x 88cm, pastel, lino print and acrylic paint on board Daphne II, 100cm x 88cm, pastel, lino print and acrylic paint on board

Daphne II, 100cm x 88cm, pastel, lino print and acrylic paint on board Daphne II detail

Daphne II detail Daphne III, 122cm x 88cm, pastel, lino print and acrylic paint on board

Daphne III, 122cm x 88cm, pastel, lino print and acrylic paint on board Daphne III detail

Daphne III detail Eve, 110cm x 40cm, pastel, lino print and acrylic paint on board

Eve, 110cm x 40cm, pastel, lino print and acrylic paint on board Daphne I, 110cm x 40cm, pastel, lino print and acrylic paint on board

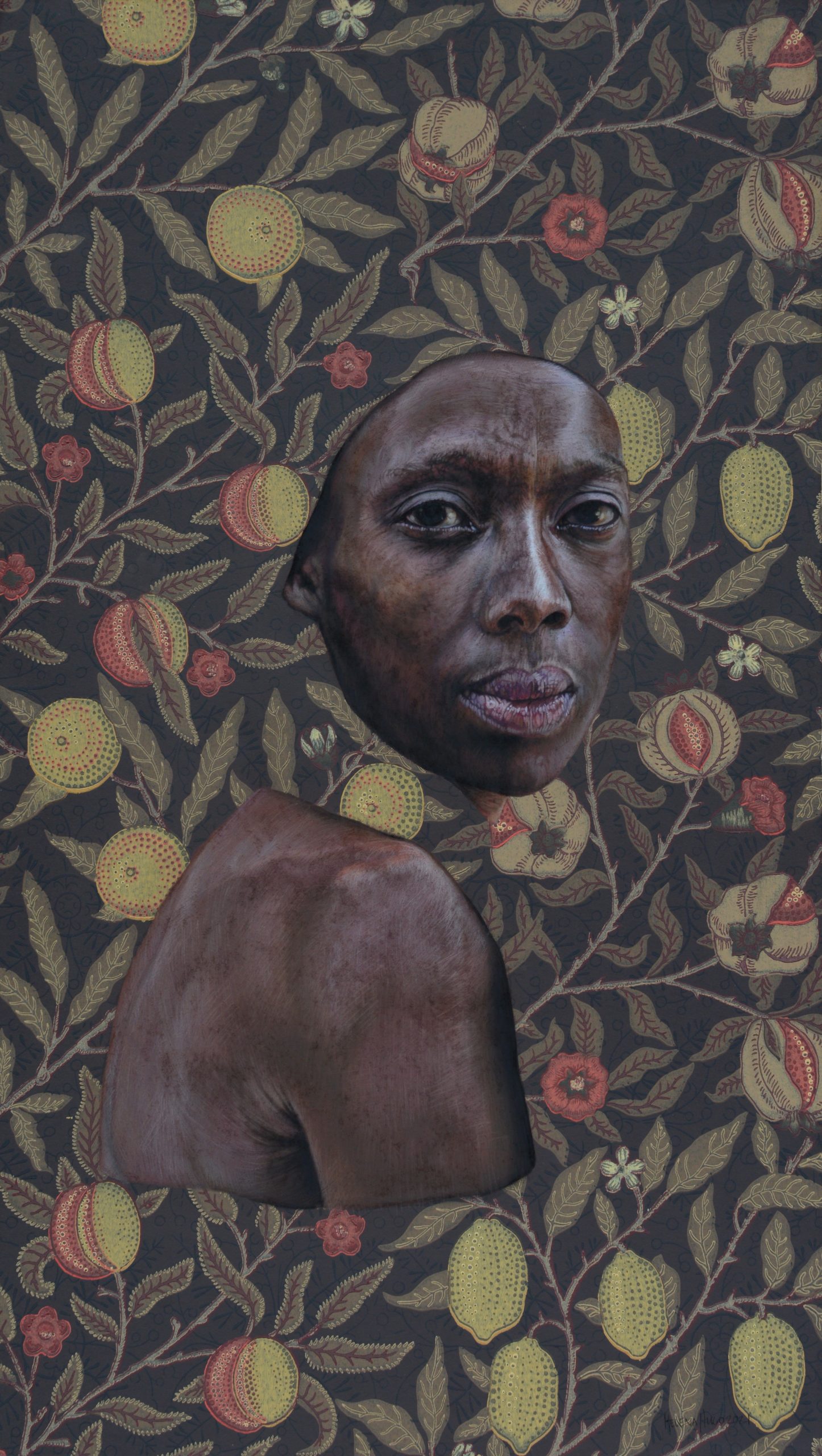

Daphne I, 110cm x 40cm, pastel, lino print and acrylic paint on board In a Man's Garden I, 90cm x 52cm, pastel and wallpaper on board

In a Man's Garden I, 90cm x 52cm, pastel and wallpaper on board In a Man's Garden I detail

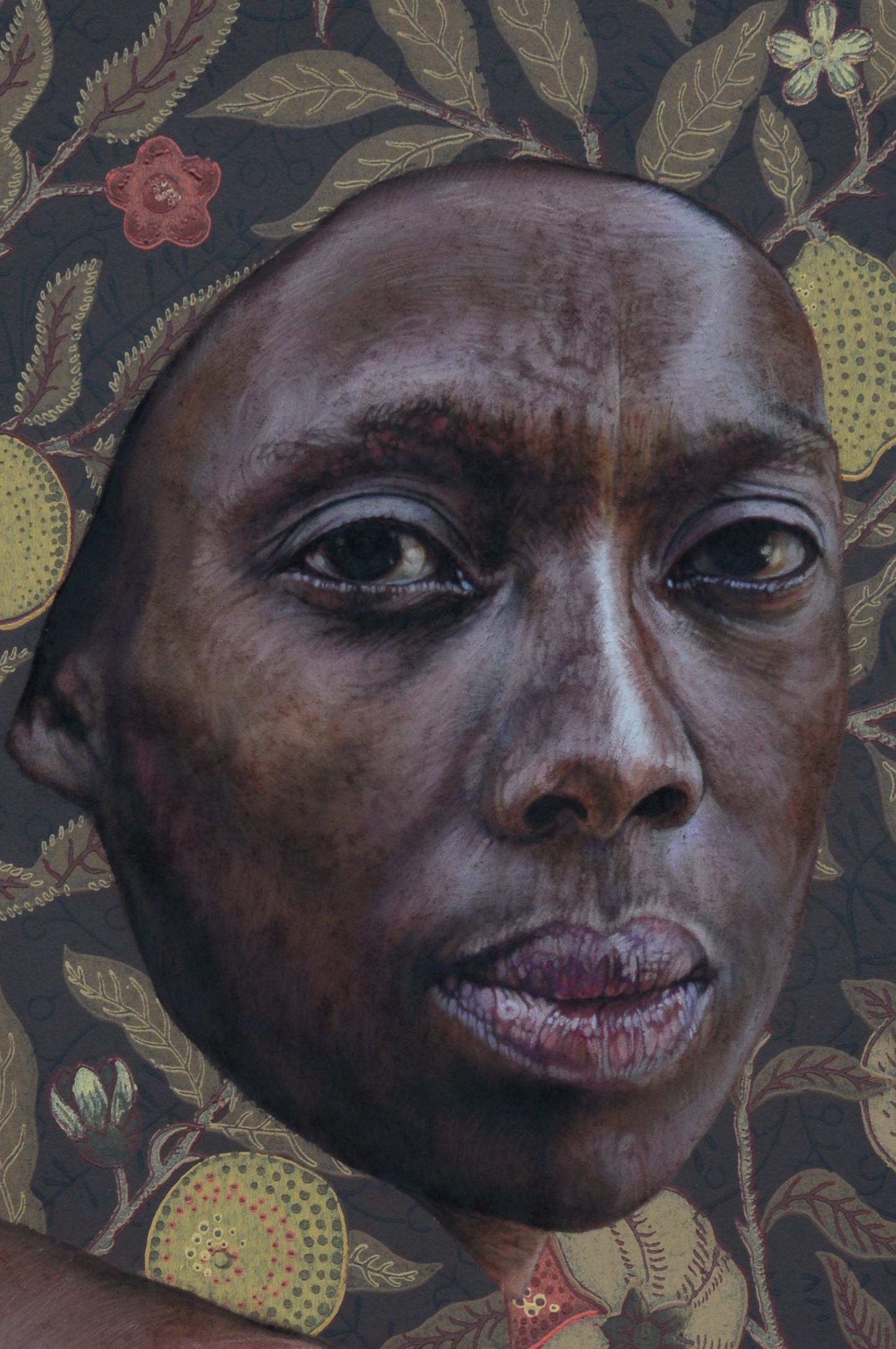

In a Man's Garden I detail In a Man's Garden II, 90cm x 52cm, pastel and wallpaper on board

In a Man's Garden II, 90cm x 52cm, pastel and wallpaper on board In a Man's Garden II detail

In a Man's Garden II detail Gaia, 160cm x 122cm, pastel, wallpaper and acrylic paint on board

Gaia, 160cm x 122cm, pastel, wallpaper and acrylic paint on board Gaia detail

Gaia detail Femme Fatale I, 75cm x 60cm, pastel on board

Femme Fatale I, 75cm x 60cm, pastel on board Femme Fatale II, 80cm x 60cm pastel on board

Femme Fatale II, 80cm x 60cm pastel on board Femme fatale III, 50cm x 137cm, pastel on board

Femme fatale III, 50cm x 137cm, pastel on board Femme Fatale III detail

Femme Fatale III detail Falling Dove I, 50cm x 45cm, pastel on board

Falling Dove I, 50cm x 45cm, pastel on board Falling Dove II, 50cm x 45cm, pastel on board

Falling Dove II, 50cm x 45cm, pastel on board Falling Dove III, 50cm x 45cm, pastel on board

Falling Dove III, 50cm x 45cm, pastel on board Marriage Proposal, 122cm x 144cm, pastel on board

Marriage Proposal, 122cm x 144cm, pastel on board Marriage Proposal detail

Marriage Proposal detail De-constructed Irises I, 23cm x 38cm, lino print and enamel paint on board

De-constructed Irises I, 23cm x 38cm, lino print and enamel paint on board De-constructed Irises II, 23cm x 38cm, lino print and enamel paint on board

De-constructed Irises II, 23cm x 38cm, lino print and enamel paint on board De-constructed Irises III, 23cm x 38cm, lino print and enamel paint on board

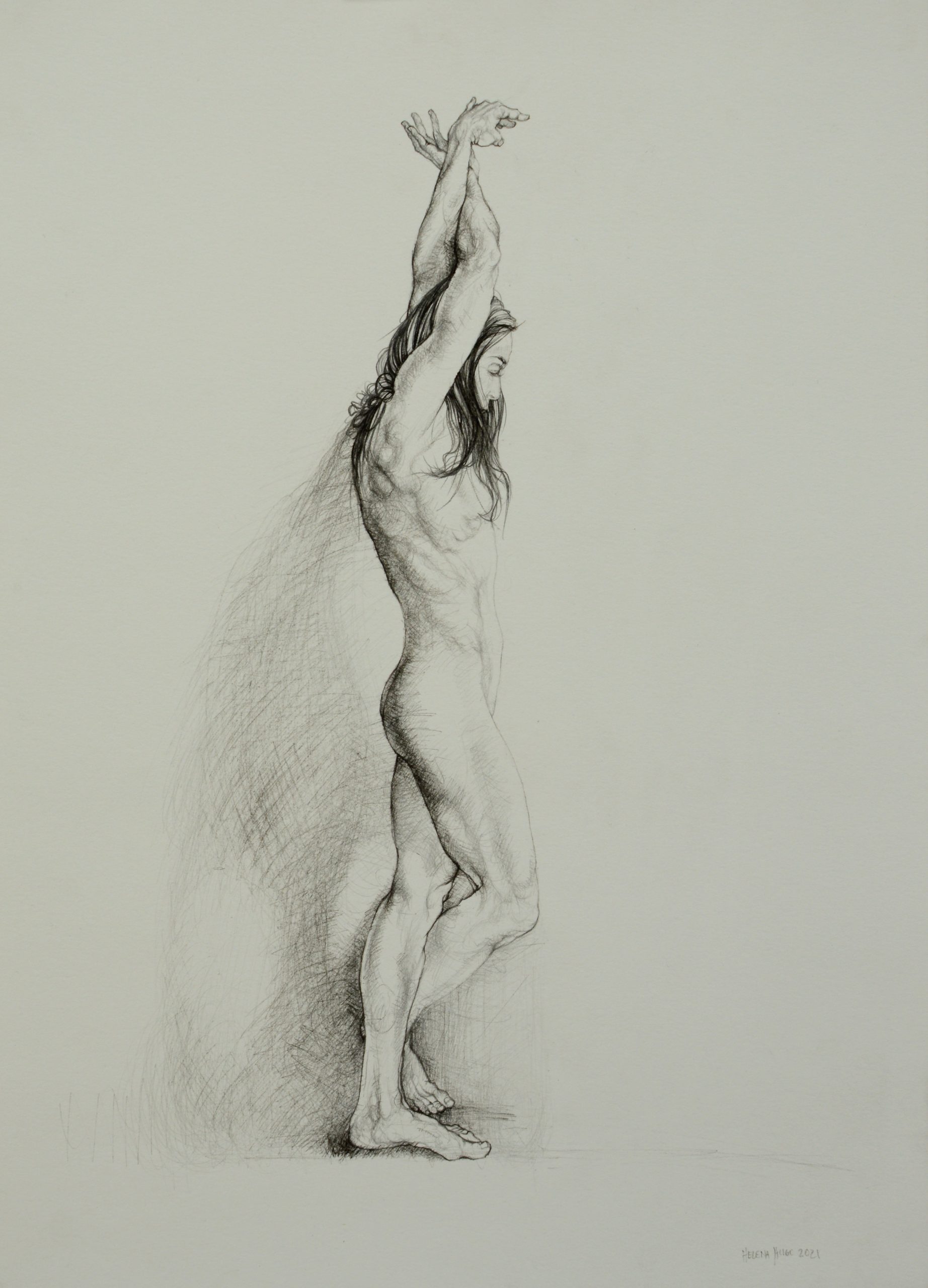

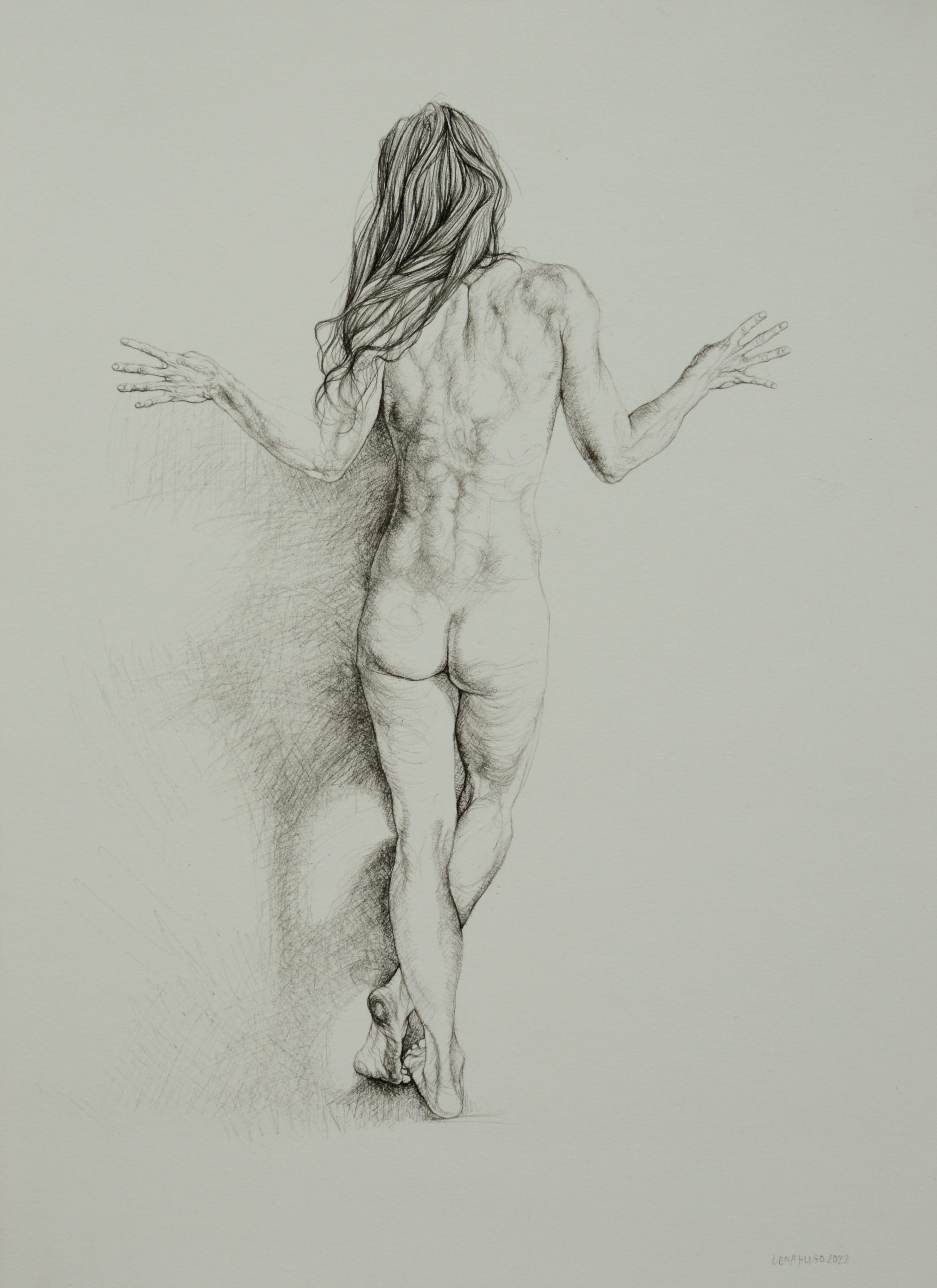

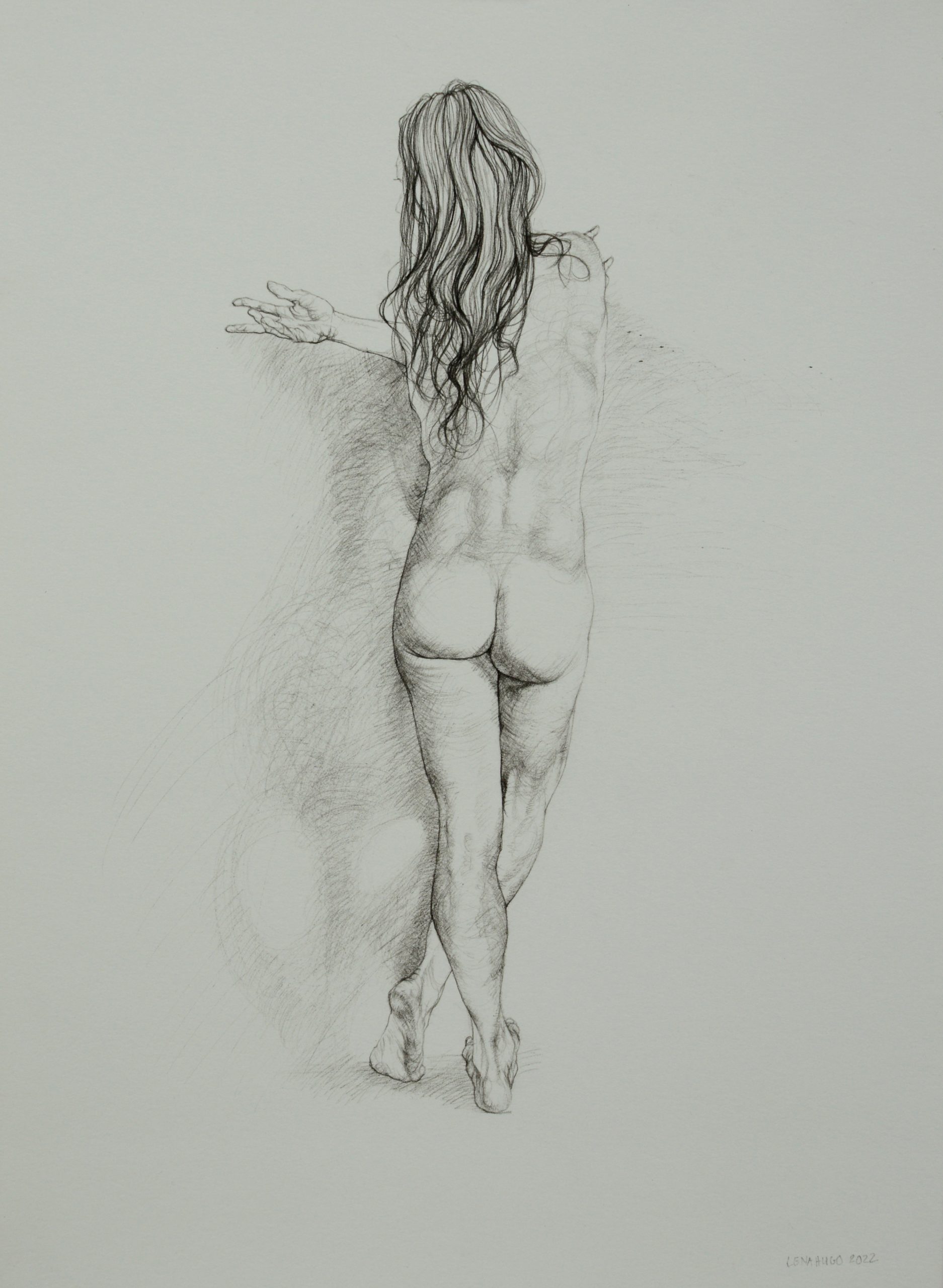

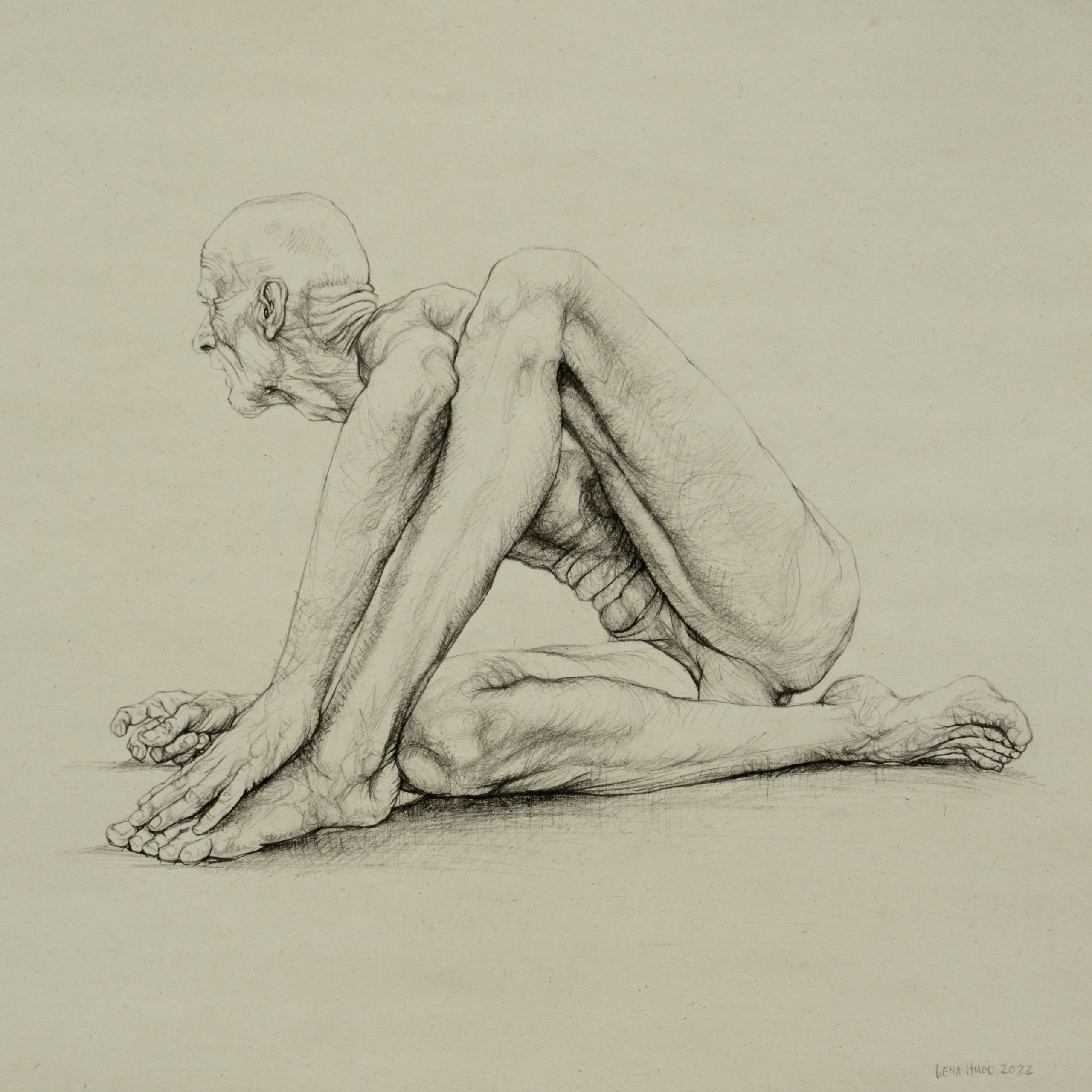

De-constructed Irises III, 23cm x 38cm, lino print and enamel paint on board Pose as a Windswept Tree I, 42cm x 30cm, woodless charcoal on paper

Pose as a Windswept Tree I, 42cm x 30cm, woodless charcoal on paper Poseas a Windswept Tree II, 42cm x 30cm, woodless charcoal on paper

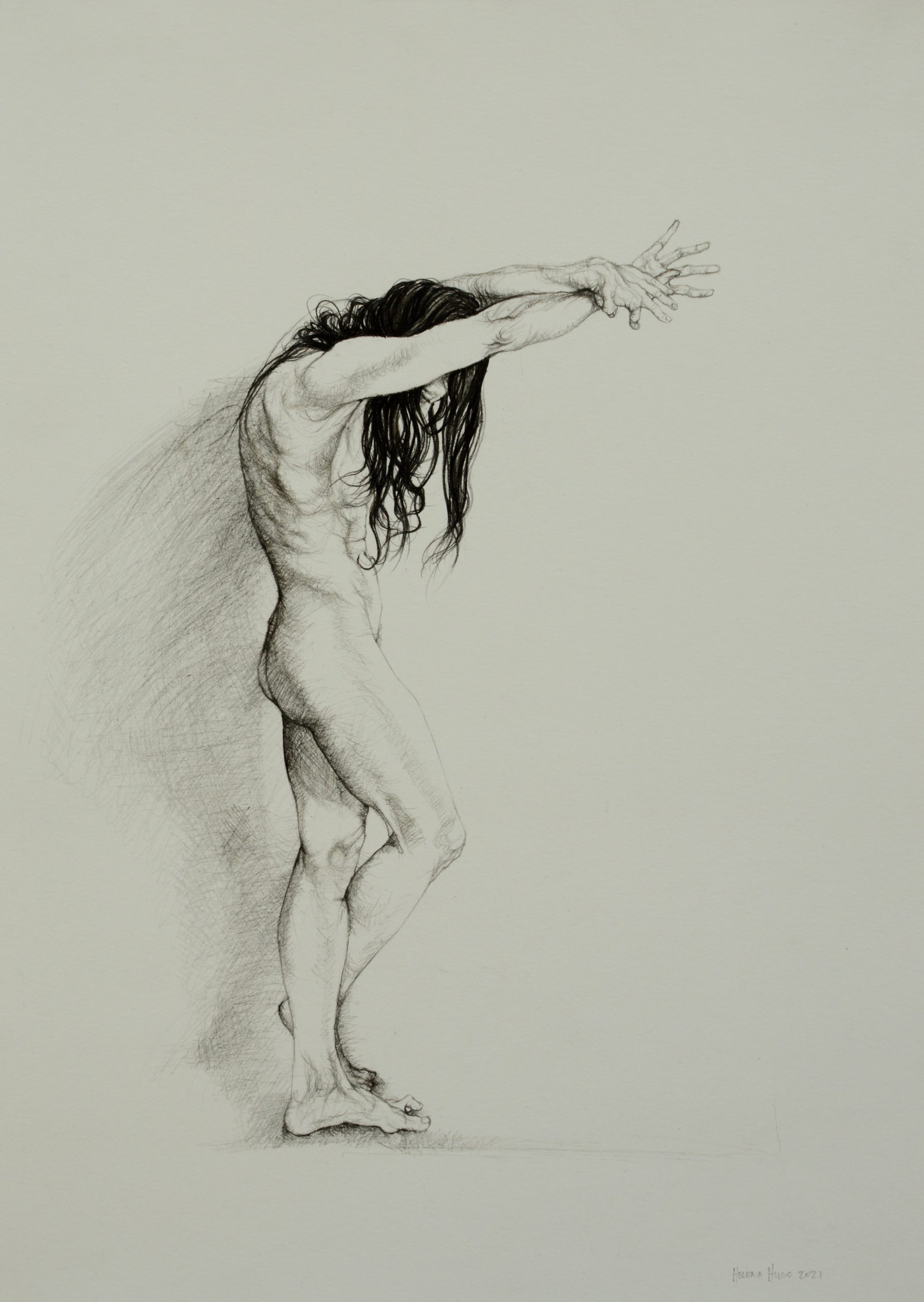

Poseas a Windswept Tree II, 42cm x 30cm, woodless charcoal on paper Pose as a Windswept Tree III, 42cm x 30cm, woodless charcoal on paper

Pose as a Windswept Tree III, 42cm x 30cm, woodless charcoal on paper Pose as a Windswept Tree IV, 42cm x 30cm, woodless charcoal on paper

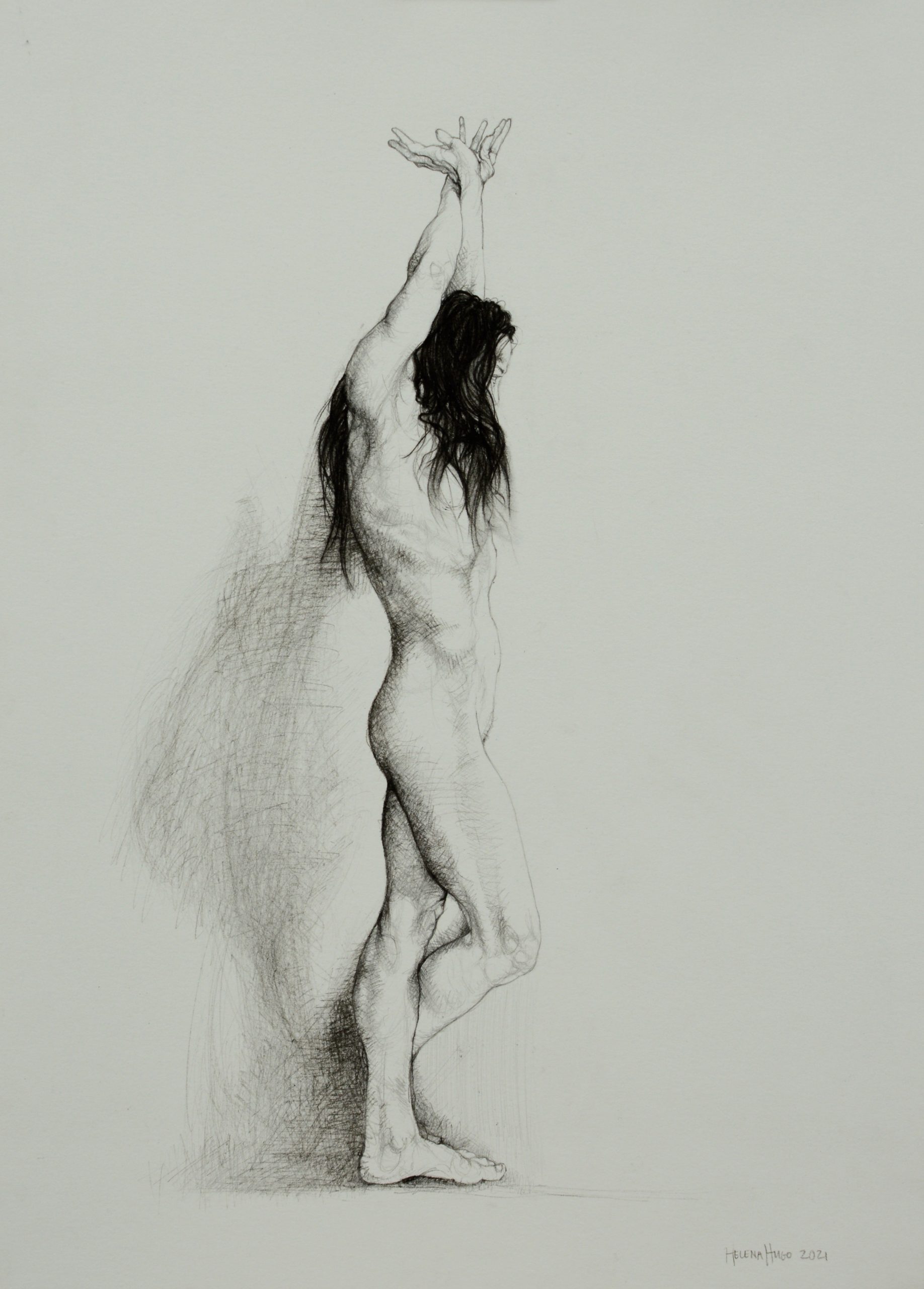

Pose as a Windswept Tree IV, 42cm x 30cm, woodless charcoal on paper Pose as a Windswept Tree V, 42cm x 30cm, woodless charcoal on paper

Pose as a Windswept Tree V, 42cm x 30cm, woodless charcoal on paper Pose as a Windswept Tree VI, 42cm x 30cm, woodless charcoal on paper

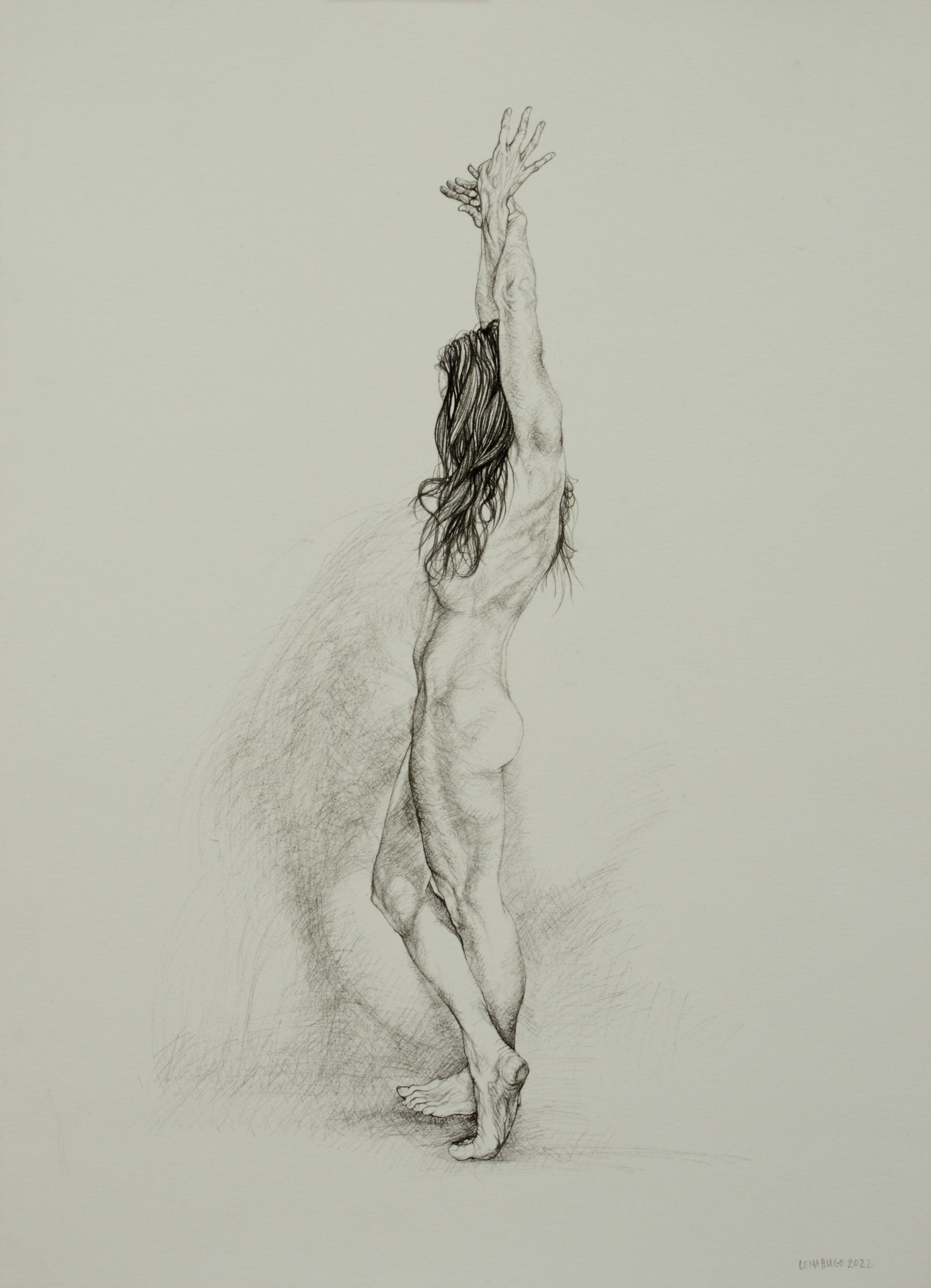

Pose as a Windswept Tree VI, 42cm x 30cm, woodless charcoal on paper Pose as a Windswept Tree VII, 42cm x 30cm, woodless charcoal on paper

Pose as a Windswept Tree VII, 42cm x 30cm, woodless charcoal on paper Pose as a Bird I, 30cm x 30cm, woodless charcoal on paper

Pose as a Bird I, 30cm x 30cm, woodless charcoal on paper Pose as a Bird II, 30cm x 30cm, woodless charcoal on paper

Pose as a Bird II, 30cm x 30cm, woodless charcoal on paper Pose as a Bird III, 30cm x30cm, woodless charcoal on paper

Pose as a Bird III, 30cm x30cm, woodless charcoal on paper The Unwelcome Visitor IV, 70cm x 94cm, woodless charcoal on paper

The Unwelcome Visitor IV, 70cm x 94cm, woodless charcoal on paper  Silence, 80cm x 60cm, pastel and oil on board

Silence, 80cm x 60cm, pastel and oil on board Contemplating Male Figure, 28cm x 23cm, pastel on sanded paper

Contemplating Male Figure, 28cm x 23cm, pastel on sanded paper The Unwelcome Visitor I, 50cm x 70cm, pastel on paper

The Unwelcome Visitor I, 50cm x 70cm, pastel on paper The Unwelcome Visitor II, 23cm x 30.5cm, pastel on sanded paper

The Unwelcome Visitor II, 23cm x 30.5cm, pastel on sanded paper The Unwelcome Visitor III, 23cm x 30.5cm, pastel on sanded paper

The Unwelcome Visitor III, 23cm x 30.5cm, pastel on sanded paper Fear Angry, 60cm x 80cm, pastel and black board paint on board

Fear Angry, 60cm x 80cm, pastel and black board paint on board